At first, going to Barranquitas felt like stepping into the world of Mad Max. The heat, the dust, the precariousness, the sense that everything could fall apart at any moment. But over time, something shifted. Maybe it was accepting my mission—to help and inspire. Maybe it was realizing that in Barranquitas, I am more myself. More of a helper. More human.

In this small town in Zulia, time isn’t measured by clocks, but by labor. The rhythm is set by the lake, the moon, the heat—and above all, by the veda, the seasonal fishing ban. When the lake goes quiet, the town listens. Nets are pulled in, motors shut down, and the community folds inward. In that silence, Barranquitas reveals itself—in its customs, its gestures, its resilience.

Days begin before sunrise. Crab fishers leave at five in the morning and return late in the afternoon. Shrimp fishers rise at two or three a.m., come back around eight or nine, then head out again in the evening, returning between nine and ten at night. Fishers who go after larger catches leave on Monday mornings and don’t return until Wednesday afternoon or Thursday morning. These extreme schedules wear down the body—and the mind. Sleep deprivation, constant stress, and the pressure to feed a family shape the character of the men in town. In that environment, toughness is the norm. Interaction between men happens through labor, through shared effort. Tenderness, though it exists, often hides behind exhaustion and habit.

The veda is not just a pause—it’s a time of fear. Families prepare during the active months, storing food, building reserves, hoping it will be enough. But it often isn’t. The veda signals hunger, anxiety for mothers, and a test for everyone. During those months, uncertainty settles into homes. Women, who already carry the weight of daily life, must stretch themselves even further. They care for children, cook, clean, pray. But they also bear the emotional burden of waiting, of silence, of worry. And while many have grown up believing their place is in the kitchen, in child-rearing, in church, some have broken that mold. Women who study, who work, who fish, who bring food home. Women who have become heroines—bathing patients, treating wounds, responding to the needs of others with action.

In Barranquitas, daily life tastes like arepas, like coffee strained through cloth, like fried fish when the veda is lifted. Women cook with what’s available—and what’s available is shared. Religion coexists with natural medicine, and prayers blend with herbal infusions gathered from the hills. Celebrations are simple but meaningful. A birthday can be a communal event, and mourning, a collective embrace that lasts for days. Children play in the dirt, teenagers gather on corners to talk, and elders tell stories that mix memory with legend. The heat is relentless—and if you wear too much makeup, the day will melt it off your face. There’s no room for appearances here. Life is lived as it is.

Even health is lived with urgency. Medications like quetiapine can be bought without a prescription. In local shops, it’s sold like any other item. It’s a reality that speaks to both informality and necessity.

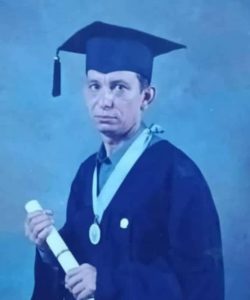

Deeply proud

Barranquitas is a town that looks at itself honestly. Its people are self-critical, but also deeply proud. Solidarity is a defining trait. There are stories of people who crossed the Darién Gap, the Rio Grande, the dangers of Mexico—waiting for fellow Barranquitas migrants. No hardship seems too great. A jungle is nothing. From the outside, people judge quickly. They talk about broken homes, about violence used to teach or to control others, without realizing that sometimes, it’s all people have ever known. But a man who wakes at extreme hours, who faces the sun, the storms, the waterspouts, and who is still known for his generosity—for walking across a continent to bring food to his family—holds deep values. They just need to be guided, recognized, supported.

I remember when we started making friends in town, everyone would wait for the bus because they knew we were coming. I’ll never forget Franklin Soto, one of three brothers who traveled to the Vatican to meet Pope Francis. Every time he knew we were visiting, he’d wait at the entrance of town to greet us with a hug, to help carry chairs, bags of food, medicine—to smile. He is the perfect example of Barranquitas’ solidarity, and of what I’ve learned there.

I believe Factor H’s present mission must be to show that there are other ways to live, to grow, to become women, to become men. That education must matter again. That we must break the tradition that says the only way to succeed is to be a fisherman, a casero (someone who transports goods to processing plants), or a beach owner (who manages small docking areas). Just as I, someone from Caracas, had the chance to see the capital, to travel to Europe, to work with people from other countries—so too can the children, parents, grandparents, the aunts and uncles of Barranquitas, discover the value of learning, of opening their minds, of knowing. It’s not just about going to school, passing classes, and graduating. It’s about understanding the power of real knowledge—the kind that breaks the grip of those who seek to manipulate, who want us limited. And this is not a criticism of the fisherman’s life. It’s a reflection of the responsibility of those of us who’ve been more fortunate. Even I, living in another state, but in the same country.

To be called “Barranquitero”

Now, my friends joke that I’m a true Barranquitero. At first, it was just a joke. Now it’s real. Because I’ve come to realize—it’s not an honor for them to call me that. It’s an honor for me to be called Barranquitero.

And now, I move to the rhythm of the veda.