On July 10, 2024, I wrote a reflection piece following the investor conference where uniQure presented the encouraging 24-month results of AMT-130, the first HTT-directed gene therapy delivered directly into the brain regions most severely affected by mutant huntingtin —the caudate and putamen.

At that time, early evidence suggested the therapy might exert a stabilizing effect on several clinical measures, including the composite UHDRS (called the cUHDRS) and its cognitive sub-scales, particularly in the high-dose group. Notably, no significant changes were seen in the Total Functional Capacity (TFC), which tracks patients’ ability to manage daily life. Still, the improvements in cognitive scales were striking, since cognitive decline remains poorly treated and is among the most debilitating aspects of the disease for patients and their families.

The results of the 24-month study, at that moment, showed a slowing of progression, with some clinical endpoints reaching statistical significance, but of uncertain clinical benefits for the patients. The changes were subtle, and they came from a small cohort—smaller still in the high-dose arm (n=9 in the high dose group, n=12 in the low dose).

Concerns at the time

At the time, my main concern stemmed from the meaningfulness of these changes, and the use of a natural history cohort, the comparative external control group, derived from TRACK-HD and PREDICT, two longitudinal natural history studies whose aim was to map the progression of the disease, as a way of defining deviation from the normal decline observed in these observational studies. While this is accepted practice in the field of gene therapy, the use of external control groups rightly raises questions about the interpretation of the results. In the 24-month analysis, an external control group of 154 patients was used, matched to the experimental cohorts in terms of baseline clinical characteristics; in addition, the selection of individuals in this natural history cohort had 2+ years of follow up, including structural imaging using MRI. The decision to include structural brain measurements probably limited the number of individuals that could be matched, a the larger natural history study of ENROLL-HD, currently ongoing in more than 150 centers and with more than 30,000 particpants, does not include MRI assessments as part of the protocol.

A turning point for the field

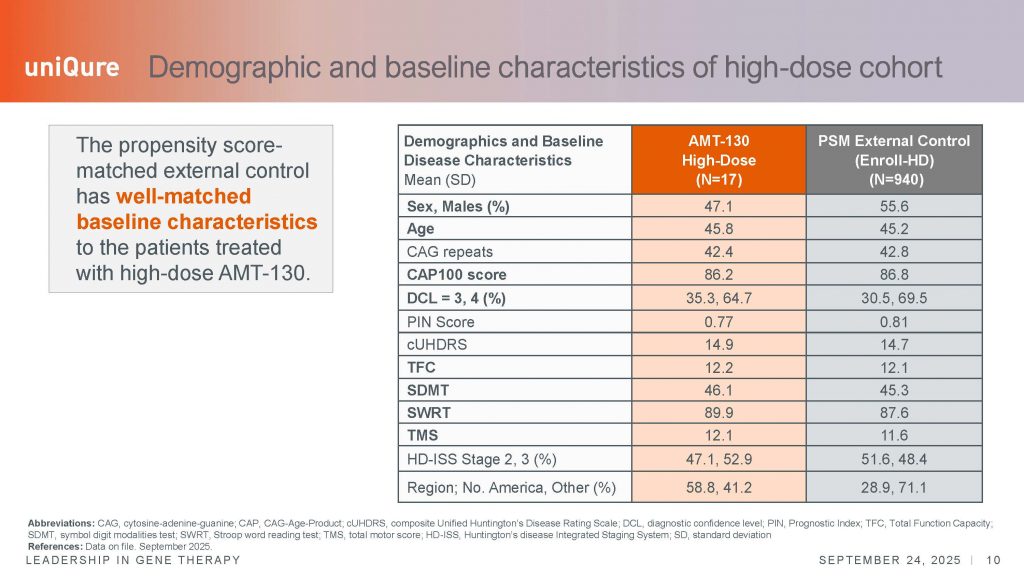

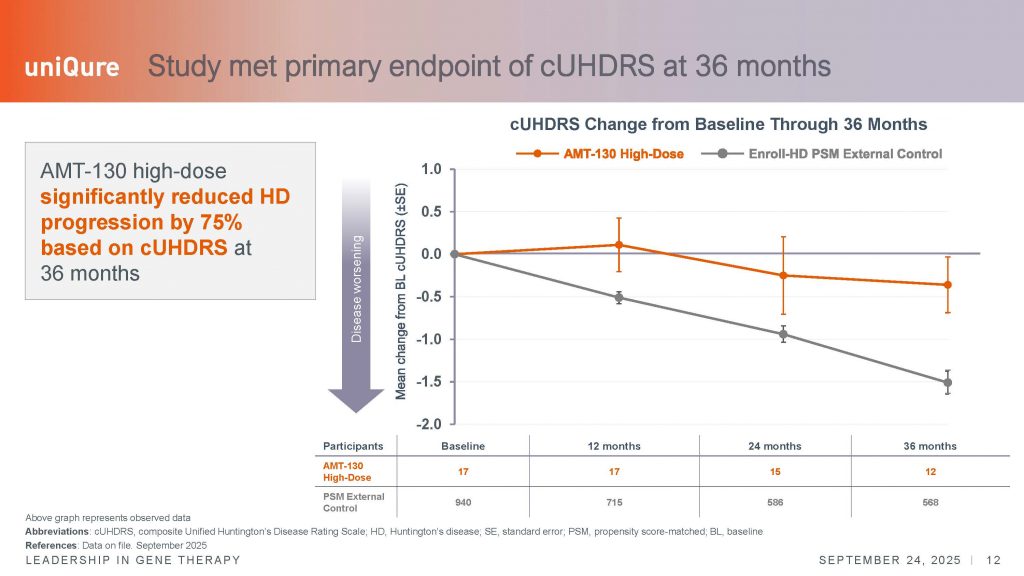

Last Wednesday, on September 24, 2025, a day that will be considered a turning point for the field of HD and, more broadly, for the treatment of neurodegenerative conditions at large, uniQure reported on the analysis of the 36-month study. By this time, there was unambiguous separation in the rate of decline between the high dose group only compared to a different – expanded- natural history cohort, this time matched from the ENROLL-HD database, and without inclusion of the MRI analysis. I can only assume that the change in the external cohort characteristics followed regulatory guidance, but it is important to keep this in mind. The 24-month data included a different external control group from the 36-month data just reported.

You can see the full disclosure AQUÍ

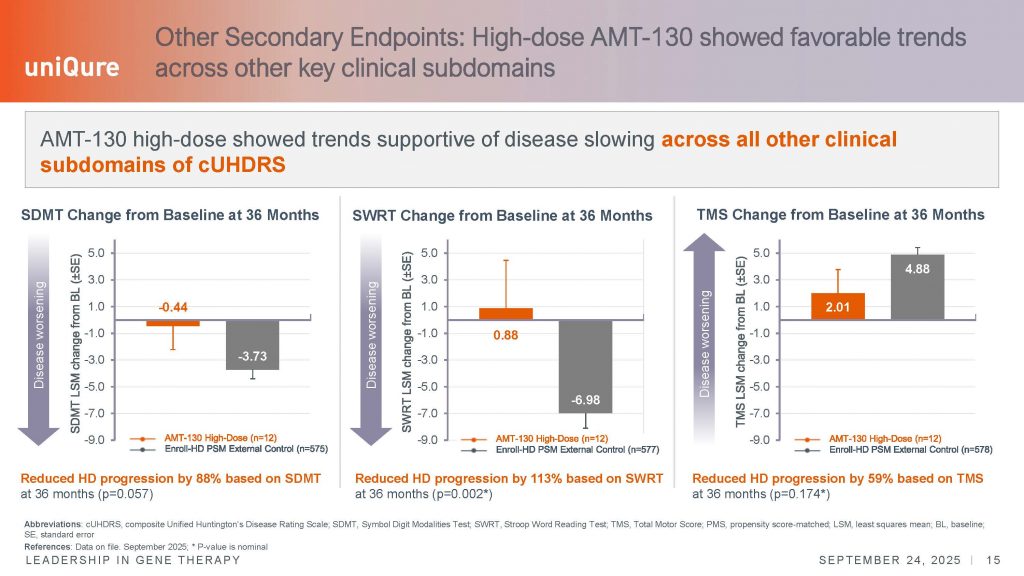

Nonetheless, in this later analysis, n=12 patients that had completed the 36-month period were included, compared with an external group of n=940 individuals at baseline, n=715 at year 1, n= 586 at year 2, and n=568 at year 3. In this comparison, every subcomponent of the UHDRS – the total motor score (TMS), two cognitive tests (SWRT and SDMT), and the TFC, showed evidence of slowing of disease, by as far as 60-113% depending on the endpoint. Overall, the data was very statistically significant. The cUHDRS showed clinically meaningful changes over this 3-year period, exceeding the 1.0 points needed to demonstrate a clinically meaningful difference in this scale.

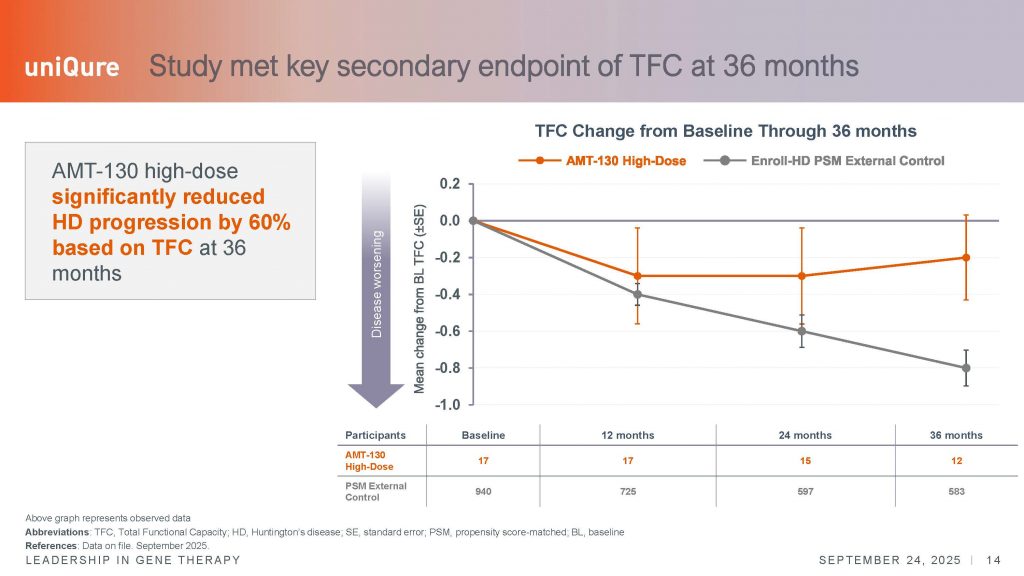

The second scale most frequently used as a registrable endpoint in interventional clinical trials is the total functional capacity scale or TFC, which measures activities of daily living and independence. This scale is probably the most meaningful to assess a real impact of an experimental therapy in the quality of life (QoL), although other scales can be explored to understand the real impact of an experimental therapy, such as QoL questionnaires, the problem assessment battery (PBA) or the global clinical impression (GCP) scales, not reported in this press release.

The convergence of improvements in these additional scales would add more weight to the meaningfulness of the effect of the AMT-130 therapy for patients and their caregivers. The changes over time in the TFC also argue for a stabilization of the disease, as patients appear not to deteriorate, compared to the external natural history cohort, and with the difference between the two groups increasing over time – from 0.3 point difference at year 2, versus a mean difference of 0.6 points at year 3. However, it is important to remember that a change of 1.2 is considered clinically meaningful, so the changes, while significant, do not reach this level of confidence.

Changes in the cognitive subscales of the cUHDRS also showed evidence of disease stabilization and slower decline, although they did not reach the threshold to be considered clinically meaningful. The SDMT (symbol digit modality test) is a scale of 110 points, and a change in 9 points is deemed meaningful – in this 36-month analysis, the change is close to that, of around a 7.8 point improvement. In the second cognitive scale, the Stroop Word Reading Test (SWRT), patients performed better, but the 10-point change was not achieved to be considered clinically meaningful. Collectively, and particularly given the fact that we have never before see positive improvements in these cognitive tasks in the context of an experimental therapeutic trial, these results are consistent with a real impact on the progression of the disease.

However, it is important to remember that the study only showed the results derived from 12 patients who have completed the full 36-months period; these individuals were in the early stages of symptomatic disease, being roughly half in the ISS-HD stage 2 and half in stage 3 at baseline. In stage-2 of the ISS-HD scale, the only changes that define this group are in the TMS and SDMT scales, so the progressive deterioration in the TFC arose sometime after their enrollment in the study. Stage-3 also includes changes in TFC and SWR scales. These scales, particularly early on in the disease, are noisy and variable, and do not always follow a straight decline trajectory at the individual level. We must keep in mind the distinction between group average analysis, and the individual trajectories of each person. Additionally, some individuals have now been in the trial for 4 years.

I strongly believe that this level of analysis will be extremely useful to report for all individuals in the study, to understand the impact of AMT-130 in the trajectory of the disease. With such a small number of individuals receiving the therapy, 1 or 2 people could be disproportionately contributing to the signals of protection demonstrated for the group average. It would be beneficial for uniQure to share such analysis as soon as possible.

Analisis of biomarkers

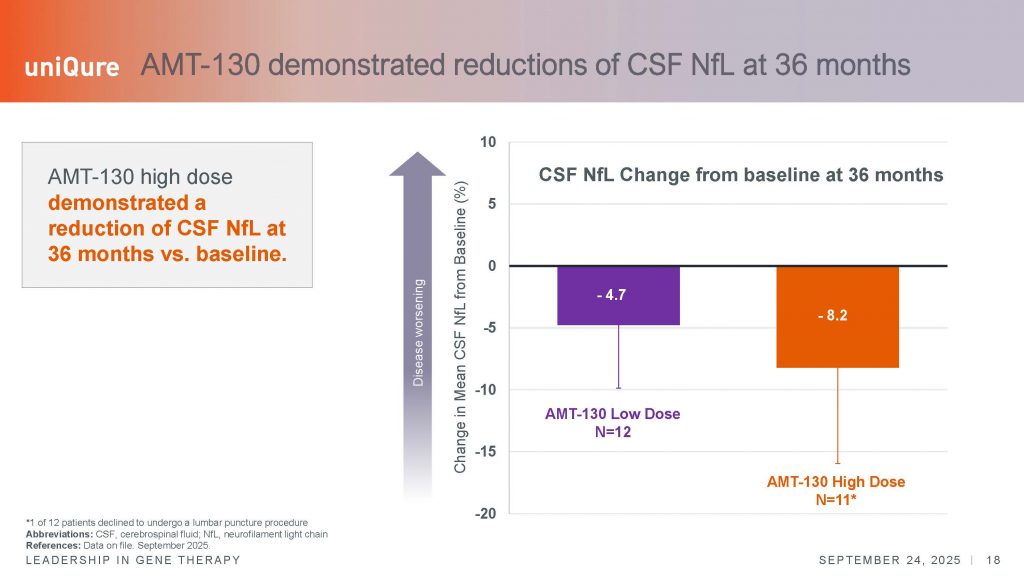

The smaller rate of decline, or the disease stabilization shown, appears supported by quantitative analysis of neurofilament light chain (NfL), a marker of degenerating axons or white matter. This analysis too showed a significant effect in the slowing of disease. Normally, NfL levels in CSF increase about 10-15% per year, whereas in this study, levels within treated individuals showed a decrease as compared to baseline levels. However, see the error bars below – this shows a large variation in the levels of NfL. Again, showing the individual trajectories would be useful to understand if some individuals respond versus others who do not. I think the field at large would also benefit from uniQure disclosing the results of the MRI analysis.

I would also argue that, given the changes in NfL, uniQure should include an analysis of striatal markers, such as enkephalin, for which quantitative assays exist. The use of enkephalin, restricted to indirect medium spiny projection neurons of the caudate and putamen, the cells that most degenerate in HD, will be more informative of a true neuroprotective activity of AMT-130. Given the importance of demonstrating changes in quantitative markers of degeneration, particularly when considering studies in the prodromal stages of the disease, uniQure might want to explore additional markers in CSF or via future neuroimaging studies. A supportive change in these markers, which appear early in the disease, would significantly increase the confidence in the disease modifying potential of this therapy.

The news of this trial has shaken the professional community, including for many of us having dedicated decades of work to reach this point. But above all, it has shaken the HD community, who were caught off guard, driving many of its members to believe that a “cure” has been found. I use that word deliberately, because this is what many now think has just happened. I have been directly contacted, as have many of my professional colleagues, by multiple family members, making me realize that this is how they feel. AMT-130, beyond the historic positive results just reported, is not yet an approved treatment. And as professionals, I always feel we must be careful about how we communicate these results so that we do not generate unrealistic expectations at this stage of clinical development.

I have to admit I watched the worldwide coverage of this historic moment with mixed feelings. It is historic—I was happy and became emotional, but at the same time, I felt concern. Clinicians and news commentators painted an overly rosy picture. While I share in the excitement about the news, we have to be very careful how we communicate to the worldwide community. The reaction echoes the excitement of 2017, when tominersen was shown to lower mutant HTT levels in CSF. Then, as now, families rushed to believe a cure was at hand, asking how quickly they could access it for their loved ones.

Communicating to families

For those of us working closely with patients, this is a communications challenge. We need to stress key facts: the therapy is not yet approved; access will not be possible for at least a year in the U.S., assuming approval by mid-2026; and no plans have been announced for Europe or beyond. Families deserve a realistic sense of the commercial path ahead.

Equally important, many currently affected patients will not benefit. By early stages of symptomatic HD, the caudate and putamen have already shrunk by about 50-60%. These are precisely the structures AMT-130 targets—and they continue to degenerate. Eventually, anatomy changes to a point where treatment becomes impossible. Understanding how the therapy intersects with individual disease trajectories, structural MRI changes, and precise neuroanatomical targeting will be critical to optimizing its use.

Access will also dominate the conversation. Costs, geography, and the need for specialized neurosurgical centers will slow availability, creating disparities that will frustrate many families worldwide. The path to broad applicability will be slow and difficult.

HTT lowering can be disease modifying

Still, last week’s results mark a turning point. The data strongly support the hypothesis that lowering HTT in manifest patients can modify disease, galvanizing the entire field. Even if not everyone will benefit, the proof of principle is there: it is possible. That is the message we should emphasize to families.

The true impact of AMT-130 will require deeper study. Neuroanatomical degeneration varies widely between individuals, and future trials in less advanced patients may show even greater benefit—though we cannot assume this yet. For advanced patients, the key question remains: how late is too late? Families do not know these nuances, but they need clarity and honesty.

This is why we, clinicians and advocates must communicate carefully. The field is advancing, not only with gene therapies, but also with splicing modulators and ASOs, each targeting different species of Huntingtin mRNA. This diversity might indeed matter. AMT-130, along with Alnylam’s program, uniquely lowers the toxic HTT1a fragment, making cross-modal comparisons essential to chart the best therapeutic strategies.

A few last words

I would like to say a few last words. We cannot forget, in moments like this, to thank the patients who courageously enrolled in this and other pioneering trials, and to the uniQure team who persevered to bring us here. I want to extend my congratulations to the team of clinicians, scientists and other staff, who made this possible. Your work is extremely important. We are living through the most significant period in Huntington’s research since the gene discovery. With hope comes responsibility: we must not allow enthusiasm to outrun rigor in how we share these news. Families’ hopes and dreams are at stake, and our communication must match the weight of that responsibility.

8 respuestas

Thank you for the thoughtful and comprehensive analysis. Two questions: shouldn’t the next phase of development, prior to submitting for approval, test this therapy against a concurrent placebo arm rather than a historical control? Second, shouldn’t we have access to CSF mHTT levels before we conclude this trial confirm HTT is “toxic”?

Very detailed analysis, and important summary Nacho. Thank you for putting the data into context, and providing a balanced and scientific viewpoint in face of what I agree was rather rosy journalism. Fantastic results for the patients in the trial on the high dose and a long way to go from a regulatory and an economic perspective for future patients. Well done to all the scientists, clinicians and team members involved and I hope to see more excellent commentary from you on this topic.

I agree almost 100 %. As to my knowledge, a clinically meaningful difference for cUHDRS has to be greater than 1.2 points – not quite reached after 3 years.

The subjective scales of TFC and TMS show a substatial placebo-effect (s. Boareto et al. 2024).

The way results were presented by two key players was exaggerated. It mislead a vast number of families, and even worse, almost all lay-organisation to believe, a cure has been found (see social media on WWW).

Thank you for your explaination of this trial. Any advancement is cause for celebration. It will always need further investigation and true confirmation of progress. As a parent of two HD+ adult children and many other family members on my husband’s side, all i can do is pray for success in their life times. Again THANK you and the HD warriors that have been willing to participate in trials. God Speed.

Hola buenas noches es Juan Camilo Gomez Hanssen

Desde Colombia en Pereira estoy muy motivado con todo lo que pasa con la investigación y que estoy esperando por favor con Paciencia que el procedimiento me llegue y logre ayudar en este viaje.

my husband, like many many more wanted me to make an appointment straight away. This news did brighten many a day I’m sure. The future looks bright.

Gracias Ignacio, seguiremos orando y esperando.

Dear Ignacio, thank you for your carefully considered appraisal. Spot on. The prospect of Uni-Qure´s success spurring investment to drive others is as exciting to me as their own achievement. More so the importance to master future communications.