What is the difference between

having no hope and having hope?

Meet Brayan, a 13-year old boy I met when visiting the town of Barranquitas, in Venezuela, in December 2018, the last time I was able to visit. This town is a forsaken, isolated village where in every corner one finds another person afflicted with Huntington’s, wandering the streets in search of food, or simply taking a walk.

Barely clothed, dirty, and essentially abandoned, patients are surrounded by kids who never seem to slow down. Chasing chickens, playing in the garbage that piles up in every corner and unused plot of land. Like clogged arteries, black waters with sewage extend everywhere in this town, surrounding homes and playgrounds. The Lake Maracaibo, flanking the right side of the town, glows in the unrelenting sun, dark and bright at once.

Dark stains of oil and tar, the products of leaky pipes from former oil rigs that sprout all throughout the lake as if mushrooms growing out of a long-dead tree, fallen in the forest of this land. The engineers and oil workers long gone because of the social and economic unrest in Venezuela, the oil remnants mark a town where the fish have died, and the livelihoods of the fishermen shattered by that which we called progress.

Children often jump in the water to escape the heat, bathing in trash, oil and water, amongst the fishing boats that enable the only sustenance in this town, the blue crab that ends up packaged and shipped abroad, mostly to consumers in the United States. The exodus of their livelihood, like the diaspora of many Venezuelan professionals, strains the prospects of a better future for the ones that remain.

The only school in the town lays dormant, all furniture stolen, the voices of the children long gone with the hot wind coming from the Lake. No school, no playgrounds, no homes to return to. Many children live and play in the dirt roads, among the trash, avoiding the never ceasing motorbikes. People driving the bikes cover their faces with black cloth, seeking shelter from the sun and the dust that never let go. Maybe they also cover their faces to not see what’s around them. The lack of hope, the poverty, the loss of dreams of a better future. A town where stories repeat themselves generation after generation, another human being afflicted with HD and dying in obscurity.

It is in this context that I saw from the corner of my eyes a little kid following us as we walked the town to see patients in their homes. He stayed at a safe distance. He looked at us wondering why we were there. I called him over, but he hesitated.

Slightly curled light brown hair, hazel eyes, sweet like caramel, a beautiful smile that shone through the dirt in his face. He wore no shoes and no shirt, only a pair of old, rugged gym shorts too big for his frame. Even though he was only eleven years’ old at the time, he had lost his mother to Huntington’s a few years back. His father? He said he was shot and killed two years ago.

We asked where he lived. He did not want to say. We insisted, we said we wanted to help.

He lived alone. Alone. At eleven.

A decaying filthy mattress lay on the floor of a two-bedroom tin-hut. We stepped over the sleeping body of a teenager who had passed out at the entry door, probably drunk or high. The door next to Brayan’s room was occupied by an unrelated family, and their room door was shut with a chain and lock. His door was not locked. Inside, there was no furniture, no bathroom, no kitchen, no clothes, no books, no pictures, nothing. It is as if his existence did not matter

How many other kids like Brayan are there in this town?

His smile is still with me today, a constant reminder of the importance of not giving up.

He followed us to our meeting with local community leaders and doctors. He came and sat on my lap, drinking my bottle of coke. A rare moment of affection and intimacy for two people who just met and connected deeply. The love I felt for him was sincere and important.

In a scientific world where we want to measure and quantify everything,how do we measure the impact that hope has in a person or in a community?

Charles Sabine has often spoken about this radical change, this perspective change, for the HD community due to the fact that the Ionis/Roche experimental drug was shown to lower mutant HTT protein levels during the Phase 2 trials, reported last year. For him, the fact that there is a sense of hope about a treatment makes all the difference.

often get asked why I bother to work in these very difficult communities… people often assume that it is impossible to change their circumstances, so why even try?

I wonder, is changing the sense of hope for one single child enough?

How many lives changed are enough lives changed?

Brayan does not read and has not been to school. He and his sister now live with a family that took them in, but he spends most of his time in the streets. I often wonder, what is it like in this town at night, when people do not have protection or a family to care for them?

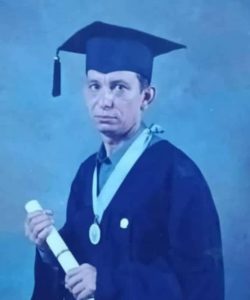

I decided to sponsor him and his sister. I said to our colleagues – treat them like they are my kids. Give them a bed, clothes, shoes, find them a teacher. Find them a home. Give them hope.

Our lives were brought together, and neither his nor my live has been the same ever since. This is how hope is created. This is how life acquires an intrinsic value. Give. Care. Stretch your hand. Make a child smile with the hope for a better future. Let him or her dream they are important.