Alex Fisher is an occupational therapist specialized in caring for HD patients from the UK; she works actively with various working groups as part of EHDN, the European HD Network. She visited for the first time the HD communities in Venezuela, together with the Factor-H team, in September 2023. Alex has written a very personal text detailing her experience, which you can read below. Alex has now become an official Factor-H European associate, and plans to return to Venezuela often to manage the Caregivers’ program managed by Factor-H and Habitat LUZ.

3 weeks in Venezuela – green eyes, pink sharpener, black gold, and La Luz

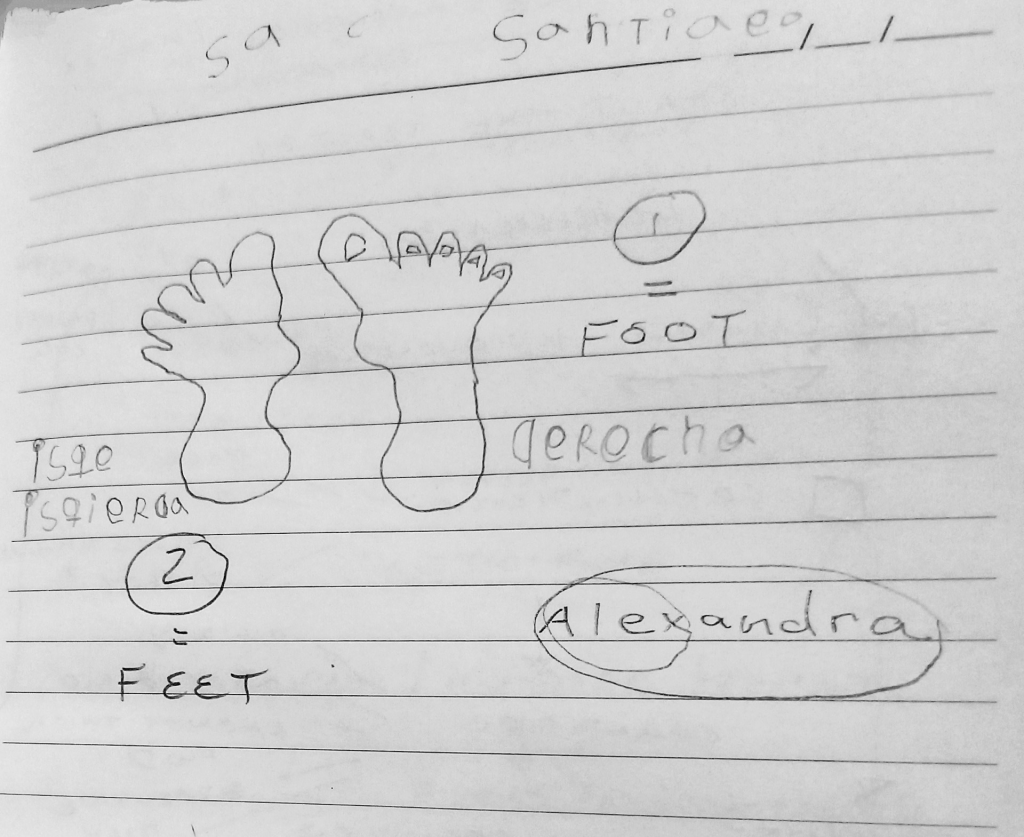

Santiago takes my hand. We’ve only known one another an hour. He’s a 10-year-old boy. ‘Will you come to my house’ he asks. We’ve been sitting drawing pictures together as he teaches me Spanish and I him English. Around us is the noise of the church fans trying to dampen the 35-degree heat set against the chatter of food distribution day in St Luis, Venezuela.

Whilst food banks are sadly a global phenomenon – this one is different. St Luis houses two of the biggest populations of people with Huntington’s Disease (HD) in the world. So, this mission organised by the joint humanitarian work of Habitat Luz and Factor-H is a vital lifeline for these families who are not only battling abject poverty but also one of the complex neurodegenerative and inherited diseases known to man.

Santiago is no ordinary young boy living in poverty. He’s a young boy whose Mum has HD for whom today’s activity provides a safety net. As we venture out of the church run by the man mountain that is Arturo the Pastor into the heat, it heightens the caustic smell of Lake Maracaibo mixed with the open sewers of the potted and rutted streets. I have to look where I’m walking to avoid turning my ankle or stepping into a small well of black gold (crude oil) which bubbles up from the earth and stains the clothes of the inhabitants. Santiago leaps ahead whilst I’m trying hard not to get distracted by the sweat dripping into my eyes or the goat and its kids bleating in the near distance.

The temperature rises to 42 degrees under the tin roof of Santiago’s home where his Mum is looked after by his grandmother. She also looks after his 4 siblings – his teenage brother almost certainly showing the clinical signs of Juvenile HD. His Mum stares at me blankly. I can see why Santiago craves connection. Despite being able to walk, her ability to communicate verbally and socially is leaving her. She’s unable to be the mother he needs her to be. HD is so much more than a problem with movement.

From that moment Santiago becomes tattooed on my heart but there are so many more Santiagos. The combined programs of Factor-H and Habitat Luz now count 450 under 12s to which they deliver care, food, clothing, and educational materials not only on distribution days but also in the constant advocacy which is ongoing in between these events. As I write this – I recall a boy with green eyes and his tiny sister, one of 7 children born to two parents with HD. Each one of them now has up to a 75% chance of inheriting the disease. I watched them on the same day as I met Santiago as they open their parcels and hear the gasp of joy at a pink, plastic pencil sharpener.

It’s easy to digress and my memories are many, but why am I here? Well, these children represent the future face of HD in this country and perhaps across Latin America as they and their families leave Venezuela in their millions having been forgotten by their government. Arturo messages Marina (the founder of Habitat Luz) in the night noting another 40 have left St Luis and no one knows where they’ve gone. We can all guess they are heading to the dangers of the border crossings with Colombia and then on into other countries or perhaps through the horrors of the Darien Gap. It’s a migrant crisis equivalent to that of Syria. So, what is left cradling the remaining HD families here is the humanitarian work of Habitat Luz and Factor-H and it is this that I asked to see. Of course, it works both ways and as an Occupational Therapist, they have asked me to explore the occupational and support needs of the families and I couldn’t do that from my privileged position in the UK.

As this is only a snapshot of my 3-week visit, I’ll fast forward to Barranquitas a pueblo which alongside St Luis has a mythological status in HD. The place where the observations of Americo Negrette and latterly Nancy Wexler and teams of scientists heralded the discovery of the gene and the cutting-edge science which flowed from there. Fast forwarding to Barranquitas is something literally you cannot do, and mythology suggests a place where abundance might live but myths are often different from reality for Barranquitas is at the end of the line. Despite what Google maps may tell you, it’s a 5-hour roller coaster ride from Maracaibo, the capital of the Zulia State and driving on the track next to the road is often easier (and more comfortable) than using the highway. Then there’s the matter of fuel for your journey. Your WhatsApp will ping into life in Maracaibo when there’s news of a fuel delivery but perhaps in La Villa (the municipal town for Barranquitas), it’s wait in your car and see and sometimes for up to 5 days. There is, by the way, no phone signal in Barranquitas and unlike St Luis there’s no running water.

The two organisations hold outpatient clinics in Barranquitas every 3 months under the cover of the basketball pitch. The organisation and administration of the usual 2-day event is through the auspices of Factor-H & Habitat Luz’s exceptionally dedicated team as they pull together humanitarian aid & medical care in one. If people with HD cannot attend the outpatient events, then the team will undertake home visits. This consists of Dr. Aura (an Adult Neurologist and a volunteer (alongside her day job in Maracaibo)) in the company of Antonio (a GP paid by Factor-H who also covers St Luis) and Carolina (an Adult Physiotherapist – a volunteer (also alongside her day job)). This is Latin America, and a home visit is never just the professionals and the patients. It’s a community visit and days later when I visited Barranquitas for the purpose I described earlier, I experienced the hubbub for myself. September’s two-day event is held at the height of rainy season and at the end of day one, having retreated to La Villa where our lodgings were, we received news that the road to Barranquitas was flooded after a storm over night and with our second-hand bus with its frayed tyres holding its group of precious cargo, the second day had to be cancelled. It will be rearranged – no mean feat.

I’m back in Barranquitas for 4 days and staying in the bosom of Atalina and her family whose home is next to the Factor-H/Habitat Luz office. I’m bunking in the same room as Yolis (the Factor-H paid Social Worker) whilst Samuel (Factor-H/Habitat driver and all-round fixer in Barranquitas) as well as Gindel (a Caracas-based documentary maker/journalist, my translator) sleep in the office. Meeting with the local team, it soon became clear to me that my prepped list of what we thought the community needed to improve caregiver assistance, and what they actually wanted was poles apart. Also, what do you do when your audience can’t read or write? What do you do when if people have the internet, it’s subject to daily blackouts as the national electricity structure grinds to a halt? Viva La Luz! is the cry that goes up when it comes back on.

Focussing on the community and the breadth of conditions in which they live, we set out to interview them and film their stories. What happened was the most natural, iterative foundation to a project which we have called ‘The Cuidadores (Carers) of Barranquitas’. Firstly, there was Selina to whom Gindel bought joy to as he danced with her, and we tried to decipher what had happened to her belongings through the buzz of mosquitoes and the many voices of her neighbours. We looked like we were leading a band through the overgrown path to her shack. Crime is close at hand here and her two sons both of whom appeared to have HD may have sold the furniture for drugs but also survival leaving her only with a string chair, a hammock, a dirty mattress, and her cat. Despite masquerading as her carers, it was the community and her Sister in Law who tended to her. It might seem like I’m skirting over the latter very serious issues, but reaction requires processing and intervention has ramifications for Selina’s safety. Both organisations have a humanitarian drive and that’s about equity of delivery which does not cause tensions elsewhere. Onwards, we met Olga and Maria and latterly Jorge a homeless man with HD who has 3 affected brothers in the same position. Jorge, sleeping in an old school building was being fed by a number of ladies who asked us for more information on his condition and wanted to help. Despite their own desperate circumstances, the compassion was genuine, and it opened our eyes to where care takes place but also by whom and what it looks like.

Over the next few days, we continued to collate the stories of people’s daily lives. As an HD professional in the UK, I meet suffering and inspiration in equal measure but here it is magnified. On one of our last visits, Gindel drew me into a darkened room. As my eyes adjusted, I was surrounded by four moving bodies in varying stages of their illness. Although the sight initially stunned me with its horror, the tenderness in which these people were cared for by a young man soon emerged. Jesus cares for his Dad, his Dad’s two Sisters and his Dad’s Brother, so in other words his two Aunts and his Uncle. He knows he is at-risk, but his faith consoles him and in the brief periods of time he has to himself, he reads and tends to the garden at the rear of the house he shares with the family. We watch as he carries his Aunts into the open air kitchen area and his Grandmother and a friend undertake precision feeding of their loved ones. He had fed his Uncle earlier who is now unable to eat fluidly as his rigidity is affecting his ability to open his jaw and therefore hold and swallow adequate nutrition. I advise Jesus on back care which seems trivial but is vital to his wellbeing. I also advise on feeding his Uncle and how to increase his hydration. I make a wish list in my head to discuss with Marina to support safer manual handling.

Silently we walk back to the Habitat Luz office. There is much to be done and as we eat together, we think and plan together. Together is the word which summarises my experiences here. I came as a stranger, a foreigner but I was never alone, and I feel like I now have a new family and as my time draws to a close in Barranquitas I’m saddened that I’m leaving them. There’s one last event and it’s the formation of the new Cuidadores and Volunteers group. There’s no meeting room to be booked but rather we all grab a plastic chair and walk to a nearby lakeside wharf and form a circle next to a group of piglets irritating the more established chickens. We talk about faith, suicide but mostly it’s about the hope of what we can achieve and love and pile in for many group hugs.

My thoughts return to Santiago. ‘When will you be back’ he asks. ‘Soon’ I say.

For a full account of the September visit to these communities please see Here

One Response

Excelente el relato de su experiencia. Bravo por Alex. será nuestra aliada por las vivencias que tuvo de la realidad de cómo viven nuestros pacientes con la EH . Un abrazo grande y que Dios la bendiga. y que nos reencontramos pronto .